WHAT IS CRITICAL POSTMODERN ART?

By Leonard Koscianski (2002)

Originally published in Tamara, the Journal of Critical Postmodern Behavioral Science.

In the midst of the postmodern art tumult of the 1980’s there emerged a group of artists whose artwork was outwardly focused and culturally critical in a broad Debordian sense. Focusing on the subjects of postmodern culture, critical postmodern artists depicted the “dark” side of the postmodern world from their multiple perspectives. They did this with well-crafted works that may communicate on a broader less “elitist” level. These artists are not neutral toward their subjects.

Examples of Critical Postmodern Art

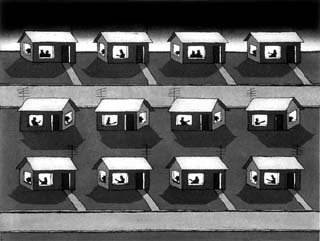

fig. 1. Roger Brown. Talk Show Addicts, 1993. Etching and aquatint, 22 1/4 x 29 ¾ in.

(Courtesy of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago)

In Talk Show Addicts by Roger Brown, a late-night view of a suburban neighborhood appears to show how completely television entertainment dominates our lives. This darkly humorous painting could be a landscape view of the world described in Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967). Identical houses contain almost identical, late-night TV viewers watching almost identical programs. The artist seems to be saying that by immersing themselves in the same TV experience these disconnected suburbanites have become isolated. Despite living in such close proximity, television watching has become the tie which binds them. They are mesmerized and dominated by the electronic spectacle. The artist has reduced the size of their homes to mere capsules for TV viewing. He takes a distant perspective and presents an idealized view of the world that they are unable to see – the world that they are collectively creating with their addiction to late-night talk shows. Additionally, his use of an idealizing style is a distancing technique which implies a more detached point of view.

In the next illustration, Untitled by Jon Swihart (fig. 2), the fragmentation of the postmodern world is suggested. A bearded young man descends from a mountain clad in ritualistic vestments of plants and vegetables. This is a religious moment. He carries a plant festooned, crosier-like staff surmounted by a rabbit’s head. He appears to be a member of a religious cult, perhaps a cult of one. The artist implies that in the absence of meta-narratives, atomized individuals may go to absurd lengths in search of meaning. Cults, fetishes, fads, and media inspired mini-trends litter the landscape of the postmodern world, especially in the artist’s native state of California. The classical oil painting style gives the image a sense of reverence – this is a religious painting. The artist’s sensitivity toward his subject indicates that he does not disparage this high priest of postmodern California. His painting is a humorous, but touching portrait of an oddly “spiritual” individual in the postmodern world.

fig. 2. Jon Swihart. Untitled, 1990. Oil on canvas, 36 x 26 in.

fig. 2. Jon Swihart. Untitled, 1990. Oil on canvas, 36 x 26 in.

(Courtesy of the Artist)

fig. 3. Charles Burns. el Borbah, 1999, pen and ink, 12 ½ x 9 ½.

(Courtesy of Fantagraphics Books )

The adult comic book artist Charles Burns illustrates a very weird postmodern realm of deformed individuals in a dark urban landscape.(fig. 3) In a world where media corporations expose us to a ceaseless avalanche of consumer products and entertainment, Burns attempts to show how this will effect who we are. These are the human products of a consumer capitalist culture. As our senses are constantly bombarded by pop commercial media (note the standing figure on the left), postmodern people become strange creatures who begin to resemble the characters that they watch everyday. Professional wrestlers like “Hulk” Hogan and “Mankind”, Barney the dinosaur, Bugs Bunny, and Batman, are the cultural figures that shape our sensibilities, our very selves. Burns has created a frightening world of postmodern people. His images seem Goyaesque in their depictions of the deformed inhabitants of a runaway consumer culture. He takes a critical stance.

fig. 4. Leonard Koscianski. Man is a Wolf to Man, 1985. Oil on canvas, 48 x 66 in.

(Courtesy of the Artist)

A media saturated world was predicted to make people the quiescent observers of the commercial spectacle.[1] However in Man is a Wolf to Man (fig. 4), artist Leonard Koscianski symbolically alludes to the dark emotional turmoil of suburbia. This painting shows a snarling canine in a suburban neighborhood of identical houses, surrounded by a cage-like network of branches. As is commonly known, the title of the work is quote from Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes. (Hobbes 1661) For many critics of the postmodern world, the individual is isolated from the product of his labor, and imprisoned in suburban sprawl. He is tantalized, and inevitably frustrated in his quest for consumer products. He is shorn of religion, ethics, and metaphysics. Even long standing customs are suspect. Using a symbolic representation of postmodern man and his world, the artist suggests that the angry, frustrated postmodern individual reverts to a Hobbsean primitive on an emotional level. The suggestion that the “Heart of Darkness” is to be found in middle America, connects the artist to modernist social critics like Sinclair Lewis and Sherwood Anderson, while his idiosyncratic symbolism seems postmodern.

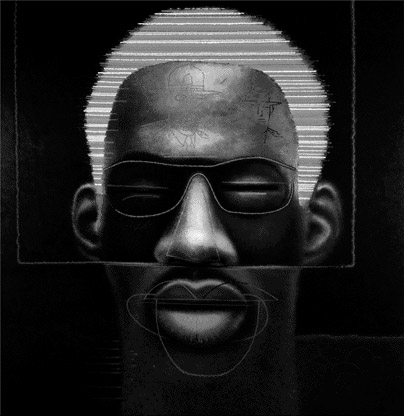

In Negrette by Ed Paschke (fig. 5), a media saturated individual, in electric colors, is transected by lines and shapes that suggest a CAD designed world in an electronic space; a space with its own form of chaos, noise, and interference. The artist depicts an individual transformed into a somewhat dehumanized hybrid of the organic and the electronic. Paschke’s subject appears electric and digital, and becomes less real. Dominated by the media he watches, his subject is in the process of morphing into the simulacra of digital space with its flickering scan lines. It is as if the artist is attempting to paint the persona of the TV viewer after a lifetime of prime time programming. Part of Paschke’s vision is the use of oil on canvas. His traditional medium detaches the observer from the electronic world. It also allows him to display his medium’s material strength in the face of the contemporary digital onslaught by creating images that are larger and more dramatic than those of the typical home television. Rather than setting up his easel in front of the TV (a postmodern stance), it is as if he has placed it on top of the TV facing the audience. If Guy Debord (1967) is correct and the viewer becomes dominated by the electronic spectacle, then Ed Paschke’s paintings may mirror that eerie transformation.

fig. 5. Ed Paschke. Nigrette, 1988. Oil on canvas, 80 x 78 in.

(Courtesy of the Artist)

Historic Background

From the Renaissance though the 19th Century, artists attempted to depict their world with greater and greater truthfulness. Each succeeding period was trying to make its vision more true in some significant way than the ones before. With the development of perspective drawing, Renaissance artists discovered mathematically precise order in the visual world, and biological structure in the study of anatomy.(Blunt, 1940) This was followed by 16th and 17th Century Baroque artists like Rembrandt or Rubens who developed naturalistic lighting, and suggestions of motion. The Enlightenment and Romantic eras with paintings like David’s Oath of the Horatii, or Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People saw the combination of didactic moral truth with increased visual accuracy.

The Modernist era of the first half of the Twentieth century was a decided break from this idea of progress toward a universal vision of truth and beauty. The modern artist championed “Art for Art’s sake”[2,] and sought to create works of “significant form” (how something is painted rather than what is painted) (Bell, 1914) or to probe the subconscious for subjective psychological insight.(Breton, 1924) This led on one hand to a search for an international language of art (abstraction), and on the other to a search for subjective truth in the subconscious world of Freudian symbols (surrealism). These two perspectives roughly corresponded to the philosophical ideas of materialism and existentialism. Be it the Cubism of Picasso, the Fauvism of Matisse, the Surrealism of Salvador Dali, or abstraction (from the red, yellow, and blue squares of Piet Mondrian to the paint drips of Jackson Pollock), one movement followed another as the Twentieth Century produced a notable series of artistic “revolutions” led by an avant-garde which rebelled against the conventions of Victorian bourgeois culture, and market capitalism.(Jameson, 1991) However like its forbearers, modernism still assumed objectivity, and the existence of valid meta-narratives. The alienation and fragmentation of modern industrial life, seen through the eyes of the alienated critic, was judged to be disturbing and harmful. Art and art praxis were seen as ways to find fulfillment in a meaningless world.

Mid 20th Century popular culture on the other hand was dominated by corporate interests, which used modern technology to transform traditional theatrical genres into mass media entertainment. As noted by the critical theorists Adorno and Horkheimer, popular entertainments dominated the subject (viewer) by bombarding the senses with a cascade of sound and images that effectively prevented thought and reflection during the entertainment experience. Additionally, the messages projected were highly consistent with the dominant capitalist viewpoint (Adorno, Horkheimer, 1944). The French philosopher Guy Debord went so far as to claim that western society had become a “Society of the Spectacle”, thoroughly entranced by a shimmering commercial illusion (Debord, 1967).

Postmodernism

The media onslaught and the decline of the Materialism and Existentialism led in the 1970’s to an era of postmodernism. Its many philosophical exponents including Deleuze, Lyotard, Baudrillard, and Foucault asserted that language was primary, if not all. Perceptions of object and subject were actually a network of semiotic clusters. There were only signifiers, no signifieds. There were no universal truths, nor were there any historical narratives that were more accurate than any others. Social structures were to be deconstructed. To the artist this implied that art would no longer involve a search for truth in an industrial world, nor be part of a grand art historical continuum. There could be no detatched observers therefore there was no purpose for an avant-garde.

For the postmodernist, art was a cluster of images and materials to be manipulated. The fragmentation of modern life was not a bad thing, in fact it was liberating. The aesthetic attributes of quality, artistic integrity, and beauty were held to be meaningless – products of outmoded meta-narratives. Artists sought to redefine art and “the artist” in a way that emphasized multiplicity of style and viewpoint. The postmodern artists appropriated symbols and images freely in the creation of eclectic art. The photographer Sherrie Levine took photographs of famous photographs, and displayed them as her own work – ironic redefinitions of originality.[3] Stylistically “Bad” paintings by Julian Schnabel or Anselm Keifer were deliberately “Bad” in an attempt to redefined notions of quality, and the value of permanence.[4] As there was no integral “self “, postmodernism relieved the artist of a concern for artistic integrity. German artist Gerhardt Richter painted in an abstract style for one painting, and a photorealistic style for the next. Performance art did away with the art object. All of these strategies required that the artist be ironically detached from his own point of view. The ideal of good craftsmanship on the part of the artist and its ethical implication of integrity and commitment was outmoded unless of course the artwork was created in a factory by someone other than the artist, as in the case of stock broker turned postmodern artist, Jeff Koons.

According to Lyotard, reality was a word game, so “playing the art establishment game” was now acceptable, even admired. Rather than being alienated and detached like their modernist predecessors postmodern artists embraced the art world establishment with enthusiasm. Unlike the avant-garde, postmodern artists avidly courted the upper class, and the mainstream media. Using public relations specialists like the advertising firm Saatchi and Saatchi, artists and their dealers (Mary Boone most notoriously) pursued curators, critics, and wealthy collectors; appeared in the pages of popular magazines; and were commissioned to create artsy full-page magazine advertisements for the likes of Absolut Vodka. Postmodern artist Mark Kostabi would ironically state that what he enjoyed most about making art was “adding zeros to the price of my paintings.”[5]

However the postmodern art world appeared contradictory. Despite touting multiplicity and acceptance, and the breaking of the boundaries between high and low art, the postmodern art world did not admit the validity of more conservative or traditional viewpoints. One would never found a National Duck Stamp Award winner, or a traditional portrait painter in a postmodern exhibition. Only multiplicity that conformed to a postmodern “look” was valid. Ironically, because of its elitism, postmodern art appeared more removed from popular culture than modernism. When the mainstream media focused on postmodern artists it was their lifestyle or the price of their paintings that was of greatest interest.(Life, 1981). As Jameson has noted the postmodern was a new “cultural dominant.” (Jameson, 1991)

Critical Postmodern

But what about broader issues of social concern? If there is no “reality”, what is suburban sprawl and its attendant alienation, smog, and three hour commutes. Without meta-narratives or “business ethics” how can one criticize offshore sweatshops grinding out mountains of running shoes? How can they be judged unethical in a world with no universal values, or judged unhealthy in the face of well-funded public relations departments that create corporate truth with advertising and well-placed press releases? In a digitized world of mainstream media, catering to commercial expectations, are there any valid independent voices?

“Critical postmodern is the nexus of critical theory, postcolonialism, critical pedagogy, and postmodern theory” (Boje, 2001) It reestablishes a critical distance between the individual and his society, and recognizes the need for an ethical examination of the material condition, and social well being of a postmodern world. It also recognizes the importance of acting on those ethical examinations. For those artists in the 1980’s and 90’s who were at odds with the ethical and aesthetic miasma of postmodernism, critical postmodern ideas came naturally.

Focusing their attention on the dark side of postmodern society, critical postmodern artists depict the sinister aspects of a media saturated, postmodern world. The critical postmodern artist depicts the fragmentation of society and the alienation of individuals as dark, problematic – weird. This outward, critical perspective is closely related to the central tenets of Critical Theory and high modernism.

Critical postmodern art is based on the postmodern assertion that all artist perspectives are valid, but unlike postmodernism, the critical postmodern holds that greater understanding of society is possible by viewing it through the lens of individual artworks or narratives. With the possibility of detatchment, a more independent point of view might be feasible. Like postmodern art, and unlike the art of the Enlightenment, critical postmodern art does not see itself as part of a progression toward an ultimate truth or beauty, nor as part of a grand art historical continuum. However it assumes that with more perspectives, more understanding is possible. This implies the recognition of a modicum of “objectivity” though it may be elusive. If some assertions are “true” – the Earth is round, Nazi Germany was inhuman, then some visual expressions might be true, or more accurately truer than others. This would seem to revive the idea of artistic detachment and notions of an avant-guarde, valid or not.

The validity of multiple perspectives does not negate truth. Because it respects the validity of the individual artist’s perspective, critical postmodern art pays respect to the integrity of that perspective more than was the case with postmodern art. It values multiple perspectives, and the integrity of each individual artist’s vision, and by extension the individual self. This departs from Lyotard’s assertion that “A self does not amount to much”. (Lyotard, 1979) This is also a departure from the postmodern art assumption that a work of art is just a move in a “language” game. Conversely, this recognition of the validity of multiple perspectives separates the critical postmodern artist from the self-centeredness of modern Existentialism. He attempts to reconcile objectivity and subjectivity. Though his vision may be largely subjective, at the same time he believes that there are other largely subjective views which when experienced may lead to understanding, or objectivity. This may be an attempt to have ones cake and eat it too, or it may be a way out of a postmodern trap.

If individual perspectives are important, then artwork, which expresses those perspectives, must be developed seriously even if the content is humorous. For this reason critical postmodern art is often more highly crafted than postmodern works, and often more accessible and communicative. The critical postmodern artist rightly or wrongly assumes that craftsmanship implies respect for the viewer, and enables artwork to communicate more effectively. The critical postmodern artist is ethically engaged in the act of creation rather than ironically detached.

As the world moves beyond the postmodern, critical postmodern recognizes the phantasm of advertising and shopping malls as a materially destructive force. It explores the effect this phantasm has throughout the world. The critical postmodern artist recognizes the need for art works which are not merely expensive status symbols, but which act as independent lenses onto a troubled world. In this praxis the critical postmodern artist recognizes the need for some form of ethics, integrity and aesthetics, without yearning for a contemporary version of the pre-postmodern world. However when one adopts a critical stance it does imply a certain moral superiority. The achiles heal of critical postmodern art may be an attempt to have both ways to be socially critical but at the same time retreat to the safety of postmodern multiplicity.

NOTES

[1] Many authors have noted the passivity of the media spectator including Guy Debord,

Society of the Spectacle (nos. 12 & 13), and Jerry Mander, Four Arguments for the Elimination of

Television (the third argument).

[2] Levine, Sherrie, After Walker Evans. Silver Gelatin Print, 1979.

[3] Benjamin Constant (1767–1834), French politician, philosopher, author. Journal

Intime, journal entry, Feb. 11, 1804, Revue Internationale (Jan. 10, 1887).

[4] Many were constructed with materials which would rapidly deteriorate. Julian Schnabel,

The Patients and the Doctors 1978 oil, plates and bondo on wood 8 x 9 ft..

Anselm Kiefer, Nigredo, 1984, Oil, acrylic, emulsion, shellac, and straw on

photograph, mounted on canvas, with woodcut, 130 x 218 1/2 in. (330 x 555 cm)

Philadelphia Museum of Art. The author saw straw lying underneath Kiefer’s paintings

during his 1982 exhibition at the Mary Boone Gallery.

[5] Kaufman, Edward. “‘Con Artist’ Mark Kostabi: On the Make and Making It,” New York

City Tribune, 4/26/88, p. 14.

REFERENCES

Adorno, Theodor & Horkheimer, Max (1944). Dialectic of Enlightenment. The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception. New York: Continuum, 1976.

Boje, David (2001). What is Critical Postmodern Theory. http://cbae.nmsu.edu/~dboje/pages/what_is_critical_postmodern.htm

Bell, Clive (1914). Art. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Blunt, Sir Anthony (1940). Artistic Theory in Italy 1450 – 1600. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Breton, Andre (1924) & Seaver, Richard (translator) & Lane, Helen R. (translator). Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Debord, Guy (1967). The Society of the Spectacle. English translation by Fredy Perlman and John Supak, Black and Red, 1977.

Hobbes, Thomas (1661). Leviathan. Viking Press, 1982.

Jameson, Fredric (1991). Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press, Reprint edition 1992.

Kaufman, Edward. “‘Con Artist’ Mark Kostabi: On the Make and Making It,” New York City Tribune, 4/26/88, p. 14.

Life Magazine (1981). Profile of Mary Boone and her Gallery , New York..

Lyotard, Jean-Francoise (1979). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. University of Minesota Press, 1985.

Mander, Jerry. Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television. New York: William Morrow & Co, reprint edition (February 1978).

© 2003 Leonard Koscianski all rights reserved.